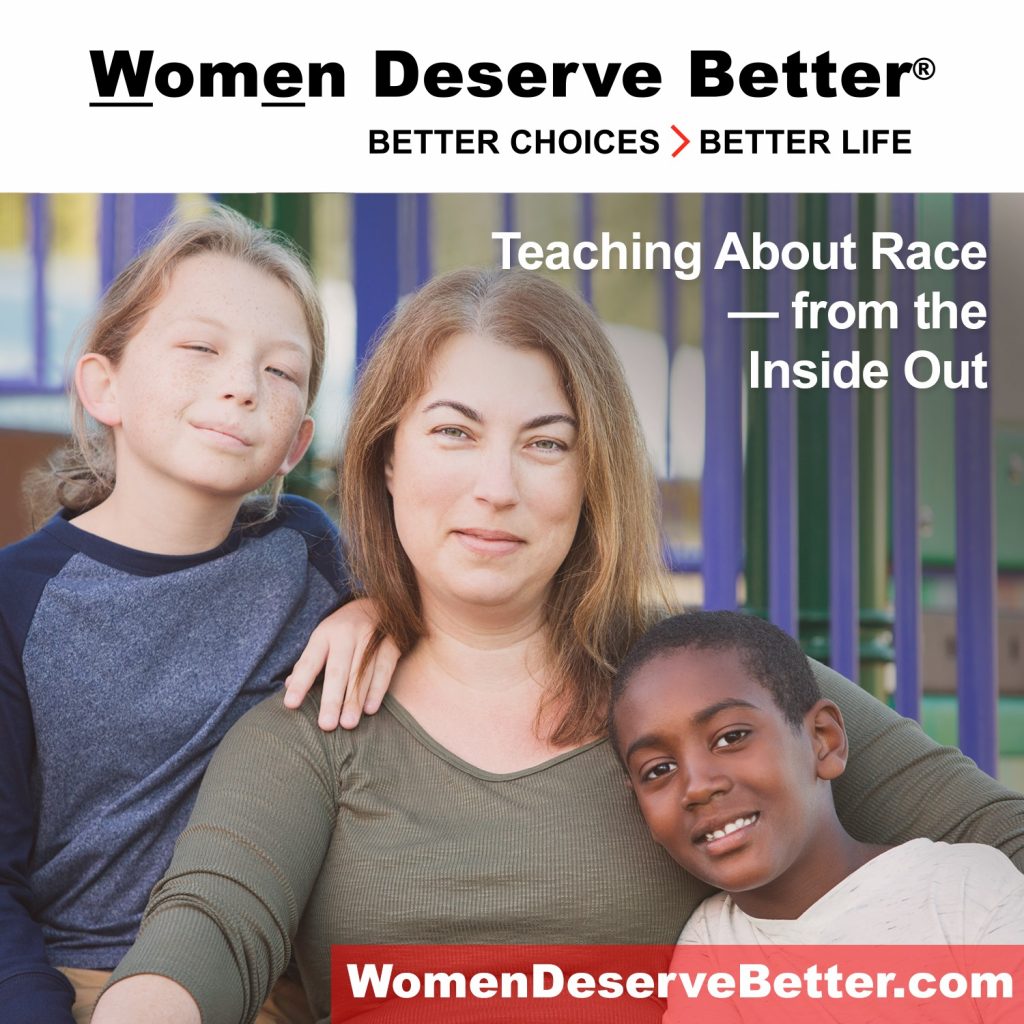

In the midst of the Black Lives Matter uprising, the disparity between my light skin tone and my son’s dark skin tone has never been more pronounced. I first noticed our difference when in the year of his birth, Trayvon Martin, an unarmed youth, was shot and killed. As I was reading the horrific news, my older boy walked in wearing a hoodie, as he often does, and the hood was up. At that time, my dark toned child was only an infant, unable to hold up his own head. I saw my sons in a very different consideration than I’d noticed before. How could I raise them to be proud of who they are when who they are is seemingly a threat to some?

Fast forward eight years — eight grueling years of difficult racial questions, jeers, and unwelcome comments — I found myself unable to exit a parking lot because of a peaceful protest. At that point, I had not yet spoken to my children about George Floyd or what had happened to him. So we disembarked, leaned on the hood of my car, and began to read the signs as they passed by, listened to the chants, and observed many a fist high in the air. In those eight years, we moved from the Deep South to a much more racially diverse area, and then we ended up in a predominantly white, New England state. As we leaned on the hood of my car that day, my son pointed out that many marchers were not black, and my white daughter pointed out that there were many black people there. We saw the same event, but how each child noticed that event taught more than our racially diverse family could ever tell.

- Honesty without details honors a child’s conscience. Children don’t need to see graphic videos to understand the horror of what happened. As I explained to them what a policeman had done, they knew that it was wrong for George Floyd to die. “Why do we say his name?” my daughter asked. He represents a change that is long overdue, and they were content with the simple explanation.

- Consequences start at home. I did not need to explain much about murder leading to a consequence. The word is used frequently in my home, because my children are not perfect. They make mistakes, and they have learned that their actions affect others and themselves. The boy/girl disparity is much more observed at their age than any racial disparity, but when I asked if it was OK for my black child to get in trouble but not my white child for the same offense, they automatically understood that race had nothing to do with the action. When I asked them if it was acceptable for me to hurt someone just because I’m grown, they fully understood that neither age nor employment excuses bad behavior.

- Build your community. When my children make young friends, I make parent friends. When I invite guests over, my children learn to be good hosts. They have more aunties and uncles than I have siblings, because we cultivate community intentionally. I’m willing to admit that I may not be their only needed resource as they grow up, and they recognize that Mommy needs her people as well. My children make Father’s Day cards for those who have no paternal connection to them and help care for and feed the bereaved. We don’t exist to serve only those with our last name. One event affects the community as a whole, and that’s why so many black people were marching that day.

- Empathy is demonstrated. In discussing why “I can’t breathe” became a mantra, they understood from example that we must listen to each other. Many a childhood tiff has led me to ask, “How does the other person feel?” Teaching them to notice another’s reaction and emotion stands out to me as the No. 1 lesson I can offer to combat the racial conflict in our society. My overreaction to a skinned knee or a splinter is not intended to coddle but to show them that we must notice and respond to another’s suffering. That’s why so many white people were marching that day.

As the marchers passed on by us and we started loading in the car to leave, I felt grateful that my children, with their differences and their variable observations, demonstrated the importance of honesty, consequence, community, and empathy. After all the chanting, horn honking, and motor revving, they were content with quiet for a while. We drove away in silence, but I knew the lessons of that day would sound in their hearts for many years to come. After all, their hearts look the same; it’s only pigment that makes them appear different. May they always be proud of themselves for the quality of character that their hearts produce.

By Yaki Cahoon